The invisible trauma of war survivors

Why today's war children could become tomorrow's forgotten survivors

What you're about to read is both a diagnosis of a hidden crisis and a call to create a solution together. Northern Irish conflict survivors are living proof of what happens when we abandon war's children after the cameras leave.

I'm looking for partners. Trauma specialists, organisations, charities, researchers, community leaders, advocates, and survivors themselves to help build awareness about this invisible crisis and work with me to start developing better approaches to post-conflict care. This is about breaking a cycle that repeats with every war.

The pattern we keep missing

Right now, across the world, children are growing up in war zones. In Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Myanmar, and countless other conflicts, young minds are being shaped by violence, displacement, and chronic fear. These children will grow into adults carrying invisible wounds that their new communities won’t understand or recognise.

I know this because I am one of those children - grown up

I spent my childhood in Northern Ireland during the conflict of the 70s, 80s, and 90s, navigating daily violence, bomb scares, and sectarian tension.

I now live in England, working in holistic healing, but I carry scars you can’t see.

Scars that most people here don’t understand or recognise.

Like thousands of others from these generations, I’m living proof of what happens when we fail to properly support conflict survivors.

I’m showing you the future

The children experiencing trauma today will be the middle-aged adults of tomorrow, wondering why no one understands their hypervigilance, their trust issues, their struggle to feel safe in the world. Unless we break this cycle.

The Northern Ireland conflict may seem like ancient history, but it’s actually a preview of what’s coming. Every current conflict is creating new generations of survivors who will need decades of support. By learning to properly care for those of us who lived through the Northern Ireland war, we can build a template for how to support all the others who will inevitably follow.

This isn’t just about Northern Ireland. It’s about creating a blueprint for post-conflict healing that could transform how the world responds to the aftermath of war.

The reality we’re ignoring

Thousands of people across the UK are living with unaddressed trauma from growing up during what was essentially a war.

The British government’s term “the Troubles” deliberately minimised what we endured. This linguistic sanitisation has contributed to the dismissal of survivors’ experiences and the failure to recognise the scale of psychological damage inflicted on multiple generations.

For those of us who relocated to the mainland, there’s an additional layer of trauma. We can often be treated as curiosities, having our experiences questioned or dismissed by people who’ve never lived through conflict.

People feel free to offer political commentary about ‘the Troubles’ without understanding what it was actually like to be a child navigating that reality. This casual dismissal, this treating our lived experience as dinner party debate material, is a form of gaslighting that compounds the original trauma.

We’re not historical artifacts to be analysed. We’re human beings still processing what we lived through.

This trauma crossed all community lines

Catholic and Protestant families, RUC officers and their families, British soldiers sent over as teenagers and young men told they were deploying to defend part of the UK, only to find themselves in what was essentially a dirty war that no one had prepared them for. Everyone was affected by this grinding, decades-long conflict.

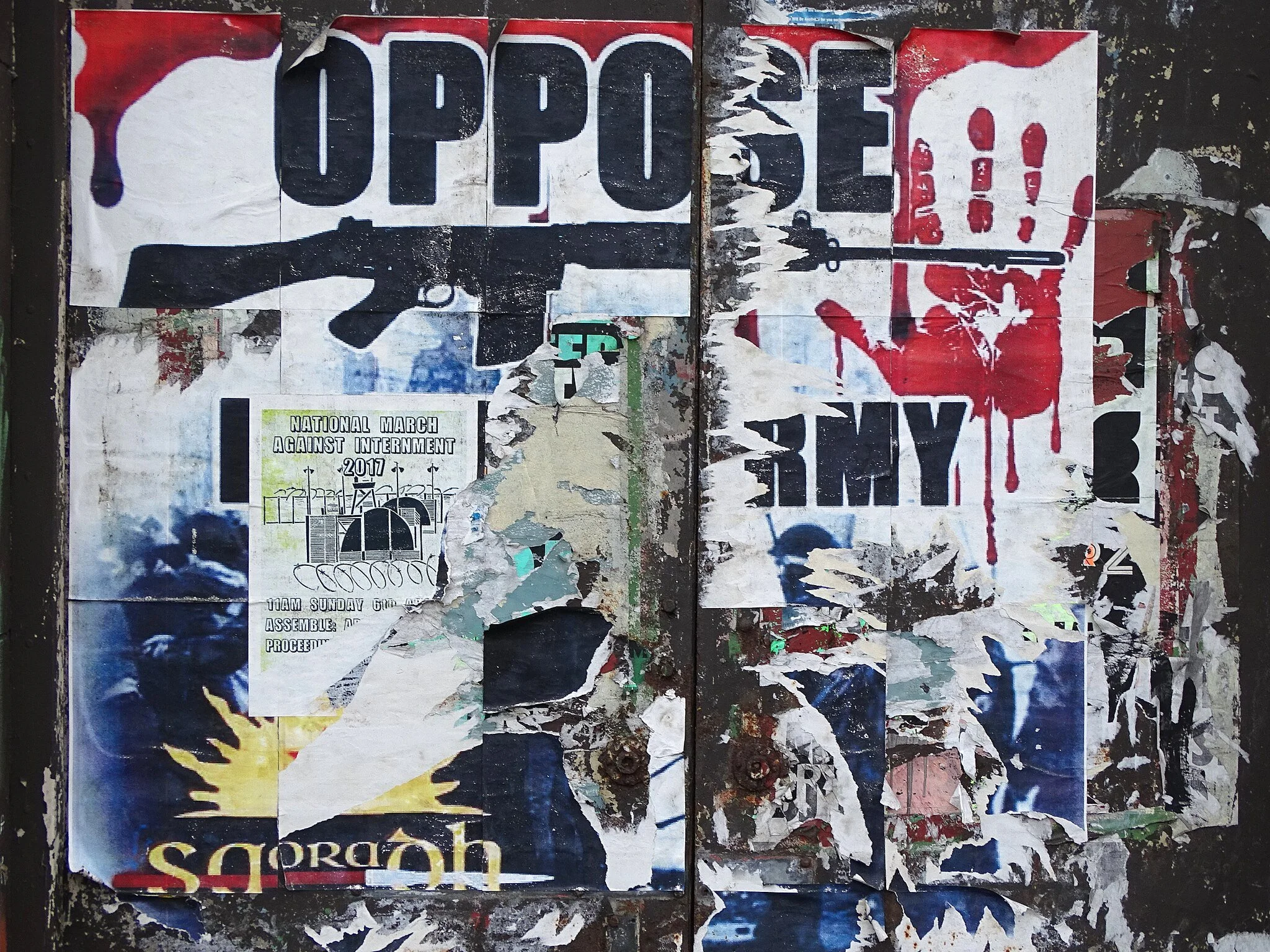

Pro Irish Republican posters from the Falls Road, Belfast

The Women who waited

Then there were the women from both communities who lived a different kind of war. The mothers who waited by windows, listening for footsteps that might never come. The wives who identified bodies at morgues, praying it wouldn't be their husband's face under the sheet. The sisters who watched their brothers get drawn into paramilitaries and felt helpless to stop the cycle.

These women developed their own patterns of trauma. Chronic anxiety that never switched off, hypervigilance around their loved ones' safety, anticipatory grief that came from living in constant expectation of loss. They carried the emotional burden of keeping families together while their own terror went unacknowledged.

They were expected to be strong, to hold everything together, to comfort their children after bomb scares while managing their own fear. When sirens sounded, every woman's heart stopped. When there was a knock at the door after curfew, every woman's world tilted.

Many of these women are still alive, still carrying that hypervigilance, still jumping at unexpected sounds, still checking the clock when loved ones are late home. Their trauma was never recognised.

Belfast at sunset

When police work became a death sentence

In 1983, Interpol named Northern Ireland the most dangerous place in the world to be a police officer - the risk factor was twice as high as in El Salvador, the second most dangerous.

The RUC became the most dangerous police force in the world to serve in, with 319 officers killed and nearly 9,000 injured.

British soldiers found themselves on constant active service for nearly 35 years. Northern Ireland now has the highest rates of PTSD among UK veterans by region, which isn't surprising given that reality.

Young working class men who thought they were going to serve in another part of Britain discovered they were walking into something entirely different. An asymmetric conflict where the enemy could be anyone.

National Memorial Arboretum, memorial way to Royal Ulster Constabulary, George Cross (the RUC is the only organisation to have been collectively awarded the George Cross).

Young lives drawn into violence

The trauma also extended to young people who found themselves drawn into paramilitary organisations through community and family pressures. Many teenage boys were recruited into the IRA during the height of the conflict, particularly after events like Bloody Sunday which drove hundreds of volunteers into the ranks.

Some came from traditional Republican families where involvement was almost expected, whilst others faced community pressure not to be seen as cowards or collaborators.

Bloody Sunday 35th year's commemoration. At the end of the march people gather at Free Derry corner where the names of the victims are recalled.

Similarly, loyalist paramilitaries like the UVF and UDA recruited young Protestant men under equivalent community pressures. These teenagers faced the same expectations to prove loyalty, defend their community, and uphold family honour.

One of the many loyalist murals in Carnhill Walk, Castlemara Estate, Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland

Whether Republican or Loyalist, these young recruits often found themselves in situations they weren't prepared for, carrying out actions they later regretted but feeling unable to leave due to family expectations, community pressure, or fear of being branded traitors.

Then there were the civilians caught between all sides - people who faced threats for not picking a side, families who were forced to leave their homes and communities when areas became too dangerous, shopkeepers who had to pay protection money to multiple paramilitary groups, ordinary people who witnessed and experienced horrific violence and lived with the constant fear of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

When neutrality meant betrayal

The psychological pressure to conform, to prove loyalty, to not let down the community or family name, trapped many people in cycles of violence and fear they hadn't chosen.

Regardless of background, religion, or political affiliation, entire generations were forced to navigate impossible choices in a conflict where neutrality was often seen as betrayal and survival often required compromising one's moral compass.

Like their counterparts across all communities, these people paid a heavy psychological price for a conflict they didn't start but were expected to navigate, participate in, or simply endure.

The Burying of this collective trauma

This isn't about supporting or condemning any side. It's recognising the human cost that ricocheted through every community, every family touched by this conflict.

Yet both the British and Irish governments, along with local politicians, have essentially buried this collective trauma. There's been a conspiracy of silence. An unspoken agreement that we should all just move on, that acknowledging the psychological aftermath might somehow threaten the powers that be.

But trauma doesn't disappear because it's politically inconvenient. It gets passed down through generations, affecting families and communities in ways that remain largely unrecognised.

Milltown Cemetery, Belfast. In 1988, mourners at an IRA funeral were attacked by a loyalist gunman called Michael Stone, killing three people. Days later, at the funeral of one of his victims, two British soldiers who accidentally drove into the procession were killed. For some of us, this was the reality of growing up here. Violence could unleash in any setting. The graves hold the dead, but trauma from incidents like this lives on in families who witnessed such violence, passed down to children who learned that nowhere was entirely safe.

The Cycle that keeps repeating

The world is always responding to the latest conflict, and rightly so. But what happens to the survivors once the news cycle moves on?

This is the pattern we see repeating endlessly: immediate crisis response, peace agreements celebrated as endpoints, then collective amnesia about the long-term psychological aftermath.

The focus on what’s trending in the news cycle, the quick social media responses, often feel superficial when you know that real healing takes decades of sustained, unsexy work that happens long after the cameras have moved on.

Northern Ireland isn’t unique. It’s a preview. Every conflict creates a generation of survivors who will need support for decades to come. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement was celebrated as an endpoint. Mission accomplished, peace achieved.

But for those who lived through the conflict, it marked not an end but a beginning: the start of a long process of dealing with decades of accumulated psychological damage. Whilst politicians moved on to post-conflict politics, we were left to navigate the aftermath with little support or recognition that healing was even needed.

Photo: Whyte’s Auctions

We’re now in our 40s, 50s, 60’s and 70s, many struggling with PTSD, hypervigilance, and relationship difficulties that we’ve never connected to our childhood experiences.

But it’s not just mental health as trauma lives in the body too. Many of us are dealing with autoimmune conditions, fibromyalgia, chronic pain and fatigue, digestive issues, and other physical manifestations of unprocessed trauma. The body keeps the score of what we endured as children, and decades later we’re still paying the price physically as well as emotionally.

The impact of childhood exposure to political violence is well-documented, yet Northern Irish survivors remain deliberately erased from trauma discourse.

Our experiences are systematically dismissed as "historical" - a calculated move to avoid uncomfortable truths about state responsibility and the long-term costs of conflict.

While survivors of more recent wars receive recognition, research funding, and therapeutic support, those who lived through 'the Troubles' are told to be grateful for peace and move on. This isn't oversight. It's a conscious political decision to bury inconvenient evidence of institutional failure and generational harm.

By learning to properly support our own conflict survivors, we can build a template for how to care for all the others who will inevitably follow.

Why this matters now

We’re at a critical moment. The generations who lived through the Northern Ireland conflict as children are at midlife, when unprocessed trauma often intensifies. Many are struggling with mental health challenges they don’t connect to their past experiences. Their own children are asking questions about family history that parents feel ill-equipped to answer.

Meanwhile, public understanding remains minimal. Most people in England know there was “trouble” but have little grasp of what daily life was actually like - the psychological impact of bomb scares as routine, of learning sectarian geography as a survival skill, of developing threat-assessment as a childhood competency.

At the same time, conflicts around the world continue to create new generations of traumatised children. The support systems we create now for Northern Irish survivors could become a model for helping others.

Family photographs holding untold stories. What you can't see in these images is how trauma travels not just through the stories that get passed down, but through the silences, and the incidents that were too painful to ever speak about. Children absorb their parents' hypervigilance, their unexplained fears, their ways of moving through the world, long before they understand why. The body remembers what the mind tries to forget, and passes that memory forward through generations.

A New approach to post-conflict healing

Working in the healing space, I see how trauma affects people but I also see how Northern Irish conflict survivors remain invisible. Currently, there’s minimal specialised support for this population and virtually no public awareness. Standard trauma services often don’t recognise the specific patterns of political violence trauma. Community support networks are scattered or non-existent, particularly for those who relocated.

I want to change that. What does that actually look like?

I'm still figuring it out, but I know we need counsellors who understand that hypervigilance isn't paranoia and that it's survival skills from childhood.

We need GPs who know that fibromyalgia might be your body keeping the score.

We need support groups where people don't have to explain why fireworks make them freeze.

We need employers who understand that checking exits isn't weird behaviour as that is what can happen when you learned threat assessment before you learned to read.

We need friends who get that crowded pubs can trigger panic attacks, not because you're antisocial, but because your nervous system is still scanning for danger.

We need partners who understand why raised voices or sudden movements can send you into shutdown mode.

We need people who recognise that struggling to trust authority figures isn't being difficult.

It's what happens when the people meant to protect you were sometimes the threat.

As someone who lived this experience and now works in holistic healing, I understand both the psychological and physical patterns of political violence trauma. I experienced direct violence, and so did my family members. I know what it’s like to learn threat-assessment as a survival skill, to carry hypervigilance into adulthood, and to live with fibromyalgia and other trauma-related conditions that Western medicine often struggles to connect to our childhood experiences.

The Northern Irish community showed remarkable resilience during decades of conflict. Now we deserve recognition, understanding, and support to heal from what we endured - and our healing journey could light the way for others.

Balleymoney, Northern Ireland

Spreading awareness of this hidden crisis

Right now, I’m looking to raise awareness about this invisible crisis and find the right partners to make real change happen. If this resonates with you, here’s how you can help:

-

Help me reach Northern Irish conflict survivors who might feel as isolated as I once did, and educate people who’ve never understood what we lived through. But also share it with anyone who cares about conflict survivors worldwide.

-

Do you know trauma charities, Northern Irish community groups, academic institutions studying post-conflict recovery, international development organisations, or refugee support networks who might want to collaborate on this blueprint for healing?

-

Whether you’re a Northern Irish conflict survivor or someone affected by conflict anywhere in the world, I’d love to hear from you. Your experiences matter and could help shape what comprehensive support looks like.

-

Follow my work, engage with this content, help me build a community around this cause that transcends borders and conflicts.

-

Help me document what works, what doesn’t, and how we can create replicable models for post-conflict healing.

This is just the beginning. By creating effective support systems for Northern Irish conflict survivors, we’re building a model that can be adapted for every post-conflict community worldwide. We can ensure that conflict survivors - not just from Northern Ireland, but everywhere - get the long-term support they deserve.

The Syrian children fleeing war today shouldn’t have to wait 30 years to get help processing their trauma. The Ukrainian families displaced now shouldn’t have to navigate healing alone. The next generation of conflict survivors deserves better than we got.

We can break the cycle and show the world what proper post-conflict care looks like.